Living It In the Streets: The Religious Films of Martin Scorsese

A look at how the filmmaker has tackled faith across his career.

One of the things I'm excited about with Killers of the Flower Moon is to see how Martin Scorsese handles Native American spirituality. Religion has always been a main topic for Scorsese, and Native traditions and beliefs are woven tightly into their culture and society.

With the movie coming out I have decided to pull this piece from behind the paywall at my Patreon. Enjoy it!

“You don't make up for your sins in church. You do it in the streets. You do it at home. The rest is bullshit and you know it.”

- Charlie, Mean Streets

We all know that Martin Scorsese is a gangster filmmaker. We all know this, it’s the general vision of Scorsese, it’s what people harrumphed about when The Irishman came out last year. “Oh great, another gangster movie from Scorsese.” Ask someone about Scorsese and they’ll tell you - he makes gangster pictures.

But he doesn’t. I mean, he has, but he’s not a gangster filmmaker. He’s made a few, but they’re strung out across his career. If you count Mean Streets as a gangster picture (which it isn’t, but let’s be open hearted here) he would go from 1973 to 1990 without making a gangster picture; in the 30 years since Goodfellas he’s made three gangster films. (No, Gangs of New York does not count) By a reasonable reckoning Scorsese has made five gangster pictures in a 53 year career spanning 25 films.

I get why we talk about him in terms of the gangster picture - Goodfellas is probably the greatest gangster movie ever made (yes, The Godfather and The Godfather Part II are better films, but Goodfellas captures something about gangsterism and its allure that the epic saga of the Corleones cannot), and his four other gangster films range from astonishing to really good. I’ll let you argue about which is which, but the important thing is that they’re all fun, except maybe The Irishman, which is repudiating the fun of his previous gangster films.

But these movies, as great as they are, don’t feel to me like the quintessential Martin Scorsese movies. These are terrific films, films I watch a lot, films brimming with innovative and exciting style. And while they contain elements of thematic concerns that I think are central to Scorsese himself (there’s a reason I started this piece with a Mean Streets quote), they don’t grapple with them in the way that his religious films do. They don’t speak as plainly, as bluntly, as specifically to his personal spiritual concerns as the trilogy of The Last Temptation of Christ, Kundun and Silence do (with Mean Streets as the prologue to the whole thing). These three films are about something that has consumed Scorsese since he was a kid: the question of how to be a person of faith and still live in the world.

Scorsese was born and spent his first few years in Corona, Queens, best known for being the home of the Lemon Ice King (seriously, if you ever get to New York in the summer head out to Corona and visit The Lemon Ice King of Corona on 108th street). But when he was about seven his parents moved the family into Manhattan, into Little Italy, and young Scorsese - who was already an awkward and nerdy kid - found himself uprooted from the world he knew and thrust into a totally different environment.

Little Italy of the 1950s was a tough neighborhood, a lower working class neighborhood made up of laborers and a couple of generations of Italians, consistently in conflict with the neighboring communities and ethnicities. And here was little Marty, asthmatic and not very physical, stuck inside unable to play sports and hang out with the rough and tumble street kids. They’d open up fire hydrants in the summer, but sickly Scorsese wasn’t allowed to get wet; instead he sat at the window and watched it all, developing the voyeur’s eye all filmmakers must have.

It was here he discovered movies, first going uptown to the theater with his father and then finding movies on TV. But before that he discovered the church. His family wasn’t religious - they were religious in a very specific 20th century Italian Catholic way, in that the home had plenty of religious iconography, statues, crosses, but the family rarely went to church. They did holidays, the big ones, but not weekly masses.

Young Marty traveled down the street more often, visiting Old St. Pat’s on Mulberry (but the entrance is on Mott, if you want to go visit it today. To give you a sense of how the neighborhood has changed that church, which did mass in Latin before Vatican II, now holds liturgies in English, Spanish, Vietnamese and Chinese). There he was stunned by not only the beauty of the cathedral, built in the early 1800s, New York’s second Catholic church, once the center of a hardscrabble Irish community the Italians would eventually push out, but he was also taken by the theatricality of the Catholic mass. He fell in love with the pageantry and the intonations, the swinging incense censers on chains, the robes and the methodical standing, sitting, kneeling.

He knew he was drawn to imagery, and so initially he wanted to be a painter. A little kid, he’d draw the Stations of the Cross in class and the nuns who taught his school, Sisters of Mercy, they’d love it. They’d love him, this little fast-talking energetic Italian kid drawn to the imagery of the church. But he soon figured out he wasn’t a painter, and he began thinking about becoming a missionary - which the nuns really loved - and then he decided he wanted to become a priest.

This is where his thematic obsessions began. In an interview in the book Once A Catholic, Scorsese relates his thinking at the time.

“And I started to say, Well, at least with a religious vocation a priest or a nun might have more of an inside line to heaven - into salvation, if you want to use that word. They might be a little closer to it than a guy on the street because, after all, how can you practice the Christian beliefs and attitudes you are learning in the classroom in your house or in the street?

“So how do you practice these basic, daily Christian - not even specifically Catholic, but Christian - concepts of love and the major commandments? How do you do that in this world?”

He made some steps towards a religious vocation, but Scorsese soon came to understand that this wouldn’t be in the priesthood - this would be in filmmaking.

“[My vocation] was harder,” he said. “I had to do it in the street. I had to do it in Hollywood.”

This became the driving question at the heart of his religious films. Religion permeates all of his movies - Who’s That Knocking At My Door’s protagonist, JR (intended, by the way, to be the hero of an Antoine Doinel-like trilogy which would finish with Mean Streets and was intended to begin with a still-unproduced script called Jerusalem, Jerusalem!) is riddled with Catholic guilt and even visits Old St Pat’s - but his three specifically religious movies (and the prologue, Mean Streets) wrestle endlessly with exactly the problem young Scorsese identified - how can you be a good Christian and still live in a world like ours? How can you navigate those things?

Scorsese came to The Last Temptation of Christ already wanting to make a movie about the life of Christ; this was always part of his vocation. Barbara Hershey gave him the book when they were filming his Roger Corman movie, Boxcar Bertha, and while author Nikos Kazantzakis was Greek Orthodox, Scorsese found a kindred spirit with the writer who wrestled with the human and divine sides of Christ.

The question of just what Jesus Christ is has been wildly debated with Christianity for millennia. Was he human, was he divine, or was he both? And when I say millennia, I mean this was an argument people were having in 200AD, and it’s an argument that has spawned heresies and gotten people killed. Kazantzakis and Scorsese seem to have a similar belief - that Christ was both God and man, but that it was the man that makes Christ special.

Says Scorsese: “If he had not within him this warm human element, he would never be able to touch our hearts with such assurance and tenderness; he would not be able to become a model for our lives.” And so this is the angle that he takes, and Christ becomes for him the ultimate question of how to live a spiritual life in the streets, as Christ must be both God and man at once.

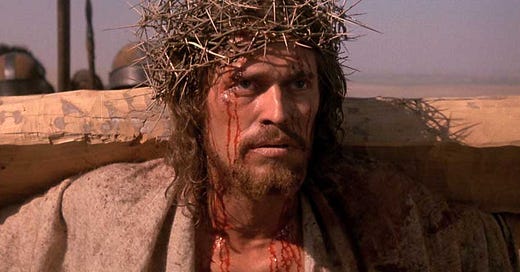

It is how Christ responds to the day-to-day challenges that defines Last Temptation; William Defoe plays Christ as a man who is, in many ways, making it up as he goes along. He is confronted by new challenges and new questions and he must come up with new answers - some of which are even contradictory in the moment. Before he begins his mission Christ is confused - he’s making crosses for the Romans upon which they will hang Jews and messiahs. When he runs into Jeroboam Christ tells him “You want to know… who my God is? Fear. You look inside me and that’s all you’ll find.”

The film was massively controversial - like, people driving trucks into theaters showing the movie controversial - and much of that controversy comes from the film’s final act. Tempted by the Devil in the form of a little girl, Jesus steps down off the cross as the moment before he is to die and he is granted a new life - he gets to walk away from being the Messiah and he gets married, has kids, has tragedy and love, works for a living, raises a family. He lives the life of a man, he is on the streets, and he dies a natural death in his bed as the First Jewish Revolt burns Jerusalem.

But he doesn’t take this option - at the last moment he snaps out of the reverie and returns to the cross, and here he whispers “It is finished,” and he dies and his destiny is fulfilled.

It is the battle between God and man inside Christ that interests Scorsese, and it is what makes the film controversial. People don’t want to examine the battle - in Christ or in themselves - and want to believe in some sort of pure godliness that they can achieve. Scorsese’s film says no, even up until his very last moment on the cross Jesus Christ was wracked with doubt and regret, that being holy was no easier for him than it was for a kid who walked out of Old St Pat’s and couldn’t help but notice the girls on the street.

Last Temptation came out at the end of the 80s, but Scorsese had been trying to make the film the whole decade. It wasn’t just a movie that fell into his lap, a concept he came across - it was truly a passion project for him (no pun intended). His second religious film, it turns out, wasn’t, and yet it perfectly encapsulates his issues and themes anyway.

Melissa Mathison, who wrote ET, became interested in the life story of the 14th Dalai Lama. Born in Tibet and raised to be both the nation’s religious and temporal leader, the Dalai Lama had the bad luck to be in charge as the Red Chinese became expansionist and moved into his country. The Communists hated the religion and persecuted its practitioners, but they knew they needed to control the faith in order to control the land. The Dalai Lama was left with a choice - stay in Tibet and either be a puppet or, more likely, be killed, or escape and try to keep alive the religion and culture of his people in exile.

Mathison lucked into extreme access to the Dalai Lama - perhaps because of her own Hollywood credentials - and she got his life story from his own lips. She wrote a script, and when she handed it to the producers she told them who she had in mind - Martin Scorsese. The producers, thinking as everybody does that Scorsese is a gangster filmmaker, were baffled, but Mathison held her ground.

It turned out to be the right choice. Kundun is a somber, sweeping and sumptuous epic, and it is straight down the middle when it comes to Scorsese’s spiritual concerns. The 14th Dalai Lama, born Lhamo Dhondup, renamed Tenzin Gyatso, is a modern man. He is fascinated by science and gadgets. He sees Tibetan Buddhism as a feudal religion in need of reform. He is a man of the spiritual and the material, a divide defined by his very job - to lead Tibetans in matters of faith but also in matters of state.

Scorsese keys into the ornate and showy aesthetics of Tibetan Buddhism, aesthetics that must remind him of what he saw in Old St Pat’s, but amplified by a hundred. The ceremony, the statuary, the flowers and the incense - in Tibetan Buddhism Scorsese sees parallels to what he himself has lovingly called the decadence of Catholicism.

And within the Dalai Lama (played as an adult by Tenzin Thuthob Tsarong) he sees a man much like himself. Not only is Tenzin split between being a man of faith and a man of the world, the demands of his position keep him locked away. Tenzin sits in a makeshift theater and is enraptured by the movies of Méliès (is Kundun set in a shared universe with Hugo?) and he stands on a balcony looking at the world through a telescope. It’s not hard to imagine that Scorsese sees much of himself in the bespectacled holy man, even if the Dalai Lama talks at a much more measured pace.

Within the story of the Dalai Lama Scorsese finds the parallels to Christ, and the ways that the divide between being in the church and being in the streets always requires some kind of sacrifice. In Last Temptation Christ must sacrifice his life as a man to ascend to Godhood, and save the world. In Kundun the Dalai Lama must sacrifice his station as godhead to remain a man and save his culture. He’s Christ in opposite, and there’s a scene where the Dalai Lama has a dream where he stands, hands out in a Christ-like pose, surrounded by the corpses of thousands of monks and nuns. They die and he lives, but the sacrifice he makes may be harder than the one Christ made - he does not get the comfort of death, he must live knowing that others died for him, that he can never return home.

Throughout the film the Dalai Lama struggles with his spiritual belief in non-violence and the terror being inflicted on his people; how to live the principals in a world where Chinese soldiers are forcing nuns and monks to have sex in the streets? His very values - including the belief that he must remain in Tibet for his people - are tested and pushed and broken. In many ways this film, which all but fell into Scorsese’s lap and was the easiest of his three religious pictures to get made, is the most in line with his own spiritual obsessions.

Before he made Kundun Scorsese was already trying to make Silence, based on the novel by Shūsaku Endō. Scorsese had discovered the novel when he visited Japan to make a cameo appearance in Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams, playing van Gogh; the novel spoke to him and he immediately moved to obtain the rights. This was the year after Last Temptation, and it would have been interesting to see Scorsese follow that up with another Christian film, but as it turned out he would not get to make the movie for twenty more years - double the time it took him to get Last Temptation off the ground. In fact the next film he would release would be Goodfellas which was probably the most defining movie of his career - which was already long by this point and already included Taxi Driver and Raging Bull.

I wonder what Silence would have been like in 1990, and what Scorsese’s career would have been like if he could have made this film instead of adapting Henry Hill’s Wise Guy. Clearly it was for the best, in just about every way, that Scorsese made Goodfellas when he did, but I also think that it’s for the best that he took so long to make Silence. Out of all of the films in this trilogy this has the most thoughtful maturity; where Last Temptation is a rough and tumble take on a Biblical epic (I love that the Apostles all talk like Brooklyn laborers) and Kundun was a prestige-y take on a sweeping Lean epic, Silence is a more integrated Scorsese film, one that marries his working class sensibilities, his interest in epic filmmaking and his dynamic cinematic visuals, all in service of a story that truly gets to the heart of his spiritual obsessions.

Set in Edo-era Japan, the film is about Portugese priests who travel to the island nation to find a missionary who, they learn, has renounced his faith in the face of torture. Japan, which is still does not exactly meet outsiders with open arms, was expressly anti-Catholic at the time, and the few believers were forced to worship in secret. The repercussions were harsh, and severe - the exact sort of repercussions Catholics would visit on non-believers in the Inquisition.

The film follows Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield), who studied under the apostate priest Ferreira (Liam Neeson) as he follows the missing priest and tries to tend to the Japanese who are persecuted for their beliefs. He finds his own faith shaken with every step he takes, and the silence in the film’s title refers to what he hears from God in his darkest moments. When he does finally find Ferreira the older man tells him Christianity is a lost cause in Japan - the people are never going to be open to it, they’re congenitally incapable of accepting the faith.

Imprisoned in Nagasaki, Rodrigues is tortured and sees others executed for their worship. He suffers as the Japanese demand he renounce his faith, which is what has kept him alive all this time, and they demand he step on a fumi-e, a special image of Christ Japanese authorities made that they would ask suspected Christians to trod upon, to prove they had no respect for the Western god. Rodrigues, who has been desperate for a message from God the whole time, finally gets one - the voice of Christ telling him to go right ahead and tread on him.

In many ways Silence is the anti-Last Temptation. Rodrigues denies his faith and lives, and marries, and spends the rest of his life in Japan. He does not martyr himself, as much as he might like to. And that, in many ways, is the sacrifice he is forced to make as he navigates the line between the spiritual and the material, as he figures out how to live in God while still walking the streets.

But Rodrigues does not truly renounce his faith; at the end, when he is dead, we see his Japanese wife furtively place in his hand a crucifix he had received when he first came to her country. Rodrigues lived every day as a Christian, but in his heart. He had to walk the streets living the things he believed without the benefit of the Church. Here, at the end of this unofficial trilogy, is the answer to the question with which Scorsese has wrestled his whole life, an answer he knew as far back as Mean Streets - you just have to do it in the streets, because that’s the only place that counts. The church, the temple, the holy ground are retreats from the reality - what truly matters is what you do when you walk out of those places, when you meet difficulties, when you are forced to live your beliefs.

That this is a trilogy of films is only due to the fact that Scorsese has not made another religious movie; he’s not young, but he’s also not done making films. I’m not certain of any upcoming specifically religious movies, but I suspect that his Killers of the Flower Moon, based on a true story about the murders of Osage tribe Native Americans to get at oil land they own will involve the spirituality of the Native peoples. But even if Scorsese never makes another explicitly religious picture these three form a beautiful triptych of what it truly means to struggle with faith. Doubt is often what we talk about, and each of these films definitely see their characters wrestle with doubt, but in the end Scorsese - even though he’s no longer a practicing Catholic - has faith. What he wrestles with is how to live that faith, how to be the kind of man he wants to be. It’s the only question really worth answering when it comes to spirituality - not whether or not you should believe, but how you should behave when you believe.

I’ve had the opportunity to meet Martin Scorsese, and I did something I never would do back in my “journalism” days - I had him sign my copy of the Criterion Collection edition of The Last Temptation of Christ. I said to him, “If church made me feel the way this movie does, I’d be at Mass every week.” When he decided not to go forward with the seminary, Scorsese made filmmaking his vocation, and in his own way he became a missionary. His works about faith have never been his most popular, but I think they’ve been impactful on the people who have come out for them. And what’s most impactful is not that they are evangelical, or that they present a dogmatic view of faith, but rather that each of these movies presents the problem of living our principals in the day-to-day world, and each of these movies affirms that it’s worth the effort. That it isn’t a question of making up for your sins in church - that it’s always done on the streets.